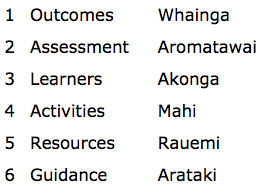

Definitions

There are many definitions of what makes a community. But if we consider a physical community such as a village, most would agree that it is not the collection of buildings that makes a village but the people who live there and the relationships between them.

We can imagine in this small French village the types of interactions that the inhabitants would have with each other and how a sense of community might arise.

But what makes it a community, and how is this different from an online community?

George Siemens states that:

A community is the clustering of similar areas of interest that allows for interaction, sharing, dialoguing, and thinking together.

Most definitions share at least this concept of communicating around shared common interests or purpose.

Check out Nancy White’s How Some Folks Have Tried to Describe Community which brings together some useful definitions. She also includes the concept of a ‘bounded’ community in a recent vieo clip: Communities, networks and what sits in between.

Some excellent readings covering key concepts are available on the website of Etienne Wenger (one of the key figures in the field) and Beverly Trayner: http://wenger-trayner.com/map-of-resources/

Online and physical communities

Siemens describes how online and physical communities share similar characteristics:

- A gathering place for diverse people to meet

- A nurturing place for learning and developing

- A growing place – allowing members to try new ideas and concepts in a safe environment

- Integrated. As an ecology, activities ripple across the domain. Knowledge in one area filters to another. Courses as a stand alone unit often do not have this transference.

- Connected. People, resources, and ideas are connected and accessible across the community.

- Symbiotic. A connection that is beneficial to all members of the community…needed in order for the community to survive.

Note: Some writers use the term ‘virtual community’ rather than ‘online community’. For the sake of simplicity, we use the term ‘online community’ here.

Types of online communities

Communities of interest

These are based around a shared professional or other interest.

Examples:

- Moodle.org: A support community for teachers (and others) using Moodle.

- LBC Support Services: Leukaemia & Blood Cancer New Zealand (LBC)’s community for patients and families living with a blood cancer or condition.

- Technology & Innovation in Education/: A community for the intersection of research and practice relating to innovation in teaching and learning.

- Google communities: Explore a wide range of communities of interest.

Social community platforms

These generally have no obvious shared interest other than meeting social needs, but may incorporate sub-groups based around specific interests.

Examples:

- Gaia: an online social community with appeal to a mainly younger audience.

- Facebook: the largest social network.

Communities of practice

These are based around sharing good practice and professional matters within a specific professional or occupation. A key reading is by Etienne Wenger, one of the primary thinkers in this area.

Examples:

- Edmodo: a community for teachers, students, administrators, parents, and publishers.

- allnurses.com: a community for nurses and nursing students.

- etwinning.net: a community for schools in the European Union.

Learning communities

Although any community can be seen as have a learning aspect, the term learning community usually refers to the incorporation of community approaches by an educational organisation into its courses and programmes.

Recent developments in technology such as Web 2.0 have given rise to some differentiation between communities and networks. The concept of a community being bounded or closed to outsiders is now being contrasted with more open networks, where the emphasis is more on connected individuals than on a community as a closed group. Chatti’s LaaN vs. Situated Learning provides a useful summary of this distinction. However, when applying learning community approaches in a course setting, we can incorporate elements of both communities and networks.

Although the principles of online communities tend to be consistent across the types, here we are primarily concerned with Learning communities and, in particular, how educators can incorporate these principles into the courses they develop and teach.

Learning communities and collaboration

Palloff and Pratt (2004) suggest that a sense of community is an essential component of collaboration, and that collaboration in turn supports the development of a community.

In other words, community and collaboration are interdependent and reinforce each other cyclically. In other words, the communication within a learning community is not just about interacting socially but about working together for some shared purpose.

Palloff and Pratt (2004) also point out that while the social interaction within a community increases student satisfaction, the collaboration provides a real opportunity to ‘extend and deepen learning experiences, test out new ideas… and receive critical and constructive feedback.’

Images

Village photo: Yvan Tisseyre / OT Vallée d’Aulps

Community-collaboration cycle: Paul Left after Palloff & Pratt (2004)

Professional development of teachers, especially in relation to integrating learning technology into the curriculum, is problematic. This scenario is intended to initiate discussion of some key issues and principles involved – what can go wrong? How do we ensure that professional development is effective?

Professional development of teachers, especially in relation to integrating learning technology into the curriculum, is problematic. This scenario is intended to initiate discussion of some key issues and principles involved – what can go wrong? How do we ensure that professional development is effective?

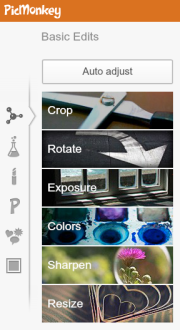

When I deliver professional development activities with teachers, I often need to point them to easy and effective online tools for working with media. Typically, they need to learn how to optimise images for the web (eg cropping and sizing), do some simple tweaks to correct exposure problems, or add some simple labels to images. Most don’t have the budget or inclination to commit to ‘proper’ image editing software such as Photoshop or Gimp.

When I deliver professional development activities with teachers, I often need to point them to easy and effective online tools for working with media. Typically, they need to learn how to optimise images for the web (eg cropping and sizing), do some simple tweaks to correct exposure problems, or add some simple labels to images. Most don’t have the budget or inclination to commit to ‘proper’ image editing software such as Photoshop or Gimp. Is connectivism a theory? I guess. But when considering its usefulness to my own teaching and learning, I have reservations.

Is connectivism a theory? I guess. But when considering its usefulness to my own teaching and learning, I have reservations.